I confess it: I love mariachi music. And Mexican food. And, OK, Mexican beer.

So, yes, this story was a hoot to write.

El Ranchito, my very favorite Mexican restaurant anywhere, ever, is long gone now. A real shame.

Originally published April 26, 1999, in The Daily Reflector | (c) 1999, 2005 Cox Newspapers, Inc. – The Daily Reflector

¡Musica para la fiesta!

Mariachi night balances tradition, a love of home and fun

Algo viejo. Rigo wrote it on a bar napkin and handed it to me.

Rigoberto “Rigo” Bernal, a cook at Chico’s Mexican Restaurant, was doing his best to explain why he was at El Ranchito Mexican Restaurant one recent Thursday night.

Rigo’s Spanish is good. My English is rumored to be OK. But as for Rigo’s English and my Spanish, forget it. So we were trying out phrases in each other’s language, attempting to kick-start a conversation.

We were brought together at El Ranchito by the rousing sounds welling up behind us. Live mariachi music has become a popular staple every Thursday night at the little red, white and green restaurant.

In Mexico, mariachi is a serious, much-loved art that, even in its modern form, dates back well into the 19th century. And for many displaced Mexicans now living in the United States, it is a link to home.

At any given time, at least a quarter of the people present on mariachi night at El Ranchito are Hispanic.

As Rigo and I flounder through our conversation, waiters dart in and out between members of the band. Spicy food to go with the spicy music.

Rigo, a native of Mexico, was there for the traditional songs: “¡Ay Jalisco No Te Rajes!,” “El Son de la Negra,” “El Rey” and many others. He was there to hear “something old” – algo viejo.

Music of tradition

The band at El Ranchito is called Mariachi Guadalajara. Unlike some of the sprawling mariachi combos you’ll find throughout Mexico, strolling the River Walk in San Antonio or playing at Latino weddings everywhere, Mariachi Guadalajara is made up of four men.

“In a place this size, you wouldn’t want more than four,” says Franceine Rees, a Thursday-night regular and long-standing mariachi fan. Eight or nine mariachis wailing away in front of you might be a little overwhelming crowded around your booth while you scarf down chips and salsa.

But even with four musicians, Mariachi Guadalajara crosses the generations: Hector Cruz, the leader, is 30; Alvaro Mara, 51; Thomas Pitayo, 26; and Mart’n Garcia, 18.

The instruments for mariachi music vary. Typically, there are violins, trumpets, a vihuela, a guitarrón and one or more acoustic guitars.

The vihuela, when strummed in the traditional style, is what gives mariachi music its distinctive flavor. It looks like a miniature guitar, except it has five strings instead of six.

The guitarrón is a boxy, oversized guitar used mainly as a rhythm instrument. It’s often plucked rather than strummed, and its back is reinforced with a wide, resonant, wooden “belly” that rests atop the musician’s own belly. It’s generally this instrument or the trumpet that people most associate with mariachi bands. Often, a “TIPS” sign will be taped near the sound hole of the guitarrón. Satisfied customers slide their money in between the strings.

A few other instruments — the harp and the guitarra de golpe, another guitar variant — are also considered acceptable for mariachi.

The charm of the music comes partly from its players’ insistence on pleasing their audience and partly from the music’s contrast: the deep notes of the guitarrón stand out sharply against the high-pitched strums of the vihuela. And the bold, brassy trumpet often follows the same melody line, note for note, as the mournful violin, giving the music a lively, bittersweet quality.

Remember your very first teen-age crush, and the little looks you used to shoot each other on the sly? Remember how those secret glances could make you feel — giddy, passionate, zesty, adventurous and oh-so-sincere?

That’s mariachi music. Except that the outfits are better.

Many bands favor the charro (Mexican cowboy) costume: ankle boots ( botines ), a sombrero, a large bow tie (mono), a short jacket (chaleco), snug pants without pockets with shiny buttons (botonaduras) up the sides, a wide belt.

The members of Mariachi Guadalajara go the charro route, with white shirts; black jackets, belts and boots; and tight black pants with silver spangles running up the outside seams. But no sombreros.

“Maybe they are too heavy,” speculates Antonio Ponce, manager of El Ranchito.

Also, says Hector’s wife, Helen Dorantes, “If they use the sombrero, they need more space.”

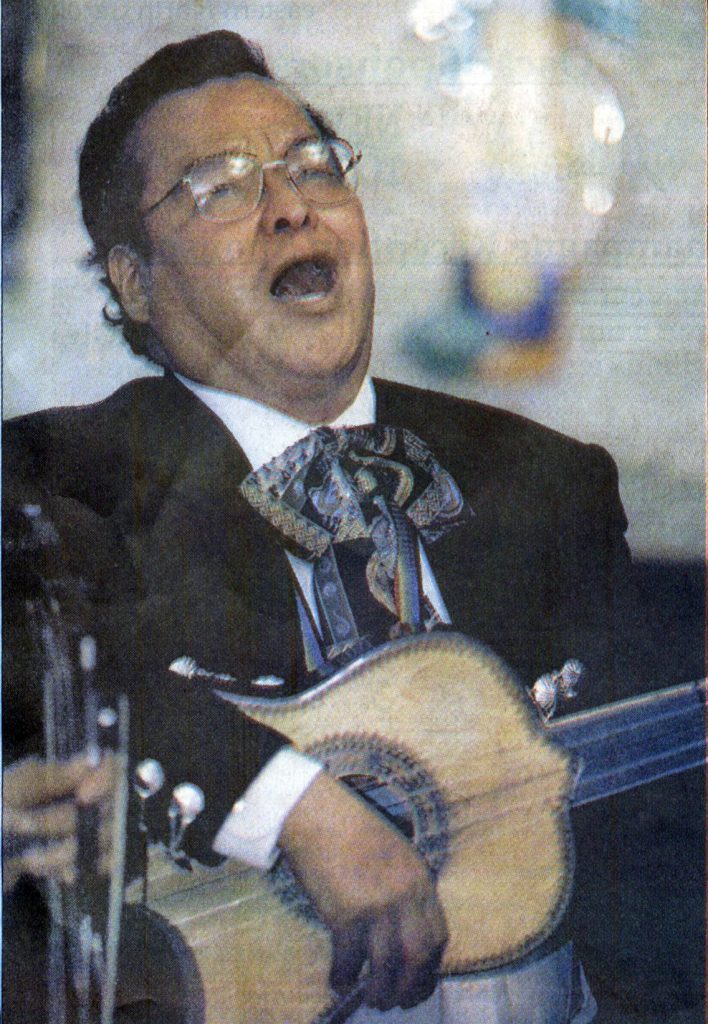

Hector plays a guitarrón; Alvaro, a vihuela; Thomas, a violin; and Mart’n, a trumpet. All members sing. All are gifted instrumentalists, though Mart’n’s warm tone is particularly noteworthy, as is Thomas’ improvisational skill.

But everything pales in comparison to Alvaro’s voice.

Since Alvaro joined the band, Franceine and her husband, Jim, make a point of requesting “Granada,” a lovely Spanish song that’s not typical mariachi fare. It puts its singer through a workout.

Alvaro is up to it.

Sitting in front of him as he launches into a song like “Granada” is asking to be overwhelmed. His strong tenor shifts effortlessly into something huge, sonorous and trembling. He can pull notes out of his toes, holding them past the point where you just know they should break. They don’t. But your heart might.

Alvaro is a small man. At times, his voice is bigger than he is.

“He sounds like José Carreras,” Franceine says.

The Spanish opera star.

“He’s got high notes that rival Plàcido Domingo,” Jim says.

The other Spanish opera star.

Music of home

Hector, Alvaro and Mart’n are from Mexico City, in the state Estado de Mexico. Thomas hails from the city of Guanajuato, in the Mexican state of the same name. Guanajuato state abuts Estado de Mexico.

There is a mariachi song called “Camino De Guanajuato” (“Guanajuato Road”). And that makes sense: Central Mexico is the heart of mariachi country.

But, says Antonio, “You can see mariachis everywhere you go (in Mexico).”

Antonio, whose Mexican friends jokingly call him “Antonio Banderas,” after the Latino heartthrob actor, is originally from Acapulco. “But the best place to hear mariachi,” he says, “is Guadalajara — since a long time ago.”

Guadalajara, the capital of the Mexican state of Jalisco, is located about 350 miles from Mexico City. Most folklorists cite Jalisco as the birthplace of mariachi music.

So the name Mariachi Guadalajara stakes a big claim: This is great mariachi music. Classic stuff.

In this case, it’s truth in advertising.

Band members now live in Florence, S.C., and make the trip up to Greenville every Thursday, driving back to Florence after the show. They work every day of the week somewhere in the Carolinas.

They first met back in Mexico, where they began playing together, says Esmeralda Black, a Spanish translator for Pitt County Memorial Hospital. Esmeralda regularly attends mariachi night with her husband, Chuck, and their high-school-age son, Nathan — who tags along for the food, he says, not for the music.

Esmeralda sits in on my interview with the band, since the group members’ English rivals my Spanish.

Hector is Mariachi Guadalajara’s manager. While other members may change on trips home to Mexico, he is a constant.

It used to be the way of things that young Mexican musicians learned the mariachi style at some family member’s knee. It sometimes still happens that way: Thomas’ father, a professional musician, taught him. And Mart’n learned from his grandfather before he started playing with his uncles.

But these days, many more aspiring mariachis are formally trained in the style and the traditional favorites — the old songs. There are specific schools in Mexico devoted to the musical form.

Modern mariachis are not only required to play by ear, but to read music, sing and improvise.

Hector attended mariachi school. Alvaro, though, learned “en la calle,” he says — on the street.

“He learned from playing in bands,” Esmeralda translates for him, “and by experience.” Alvaro has been playing now for 30 years.

But his singing is more than just the product of experience. He had some good teachers, he says. And now he teaches voice lessons himself.

“God has blessed him with this gift,” Esmeralda translates. “His working and making it a talent was not easy.”

Music of fun

On this side of the border, mariachi music is a novelty — a Mexican theme park that stops briefly at your dinner table.

It is a roving party.

“It puts you in a festive mood,” said recent mariachi convert Jennifer Yang, a student at East Carolina University. “You just want to go and sing and dance.”

We gringos who show up to hear mariachi music tend to ask for a pretty standard list of songs: the goofy “La Cucaracha”; “La Bamba,” by the late, great Ritchie Valens; something zesty by horn player Herb Alpert.

And almost always, we request the beautiful “El Cielito Lindo.”

“Ay, ay, ay, ay / Canta y no llores … “

Alvaro insists that even after playing these songs several times a night, every night, they don’t get old.

“Just like everything in life, you have to enjoy what you do,” Esmeralda translates for him. “And they enjoy what they do.”

Alvaro says that seeing the audience happy keeps things from getting dull for the musicians.

For many gringos who turn out regularly for the mariachis, the music is reminiscent of trips out West, or south of the Rio Grande.

Jim and Franceine Rees recall a trip to Tijuana a few years ago, where they fell in love with the music.

It’s uplifting, Franceine says. “It’s happy music.”

“It’s very emotional,” Jim adds. “Full of fire. It’s the music of the Mexican people.”

Alvaro agrees — mostly.

He insists that mariachi music is more than just a traditional form; it’s a vital musical style like any other. It grows; it changes, he says.

In between the old stuff, there is always room for algo nuevo. Something new.

<Page likes lost from original blogsite>