My family, on my father’s side, is Ukrainian and Slovak; his parents were first-generation Americans, straight off the boat. So writing this story, back in 2005, quickly became very personal for me, despite my trying hard to not let it be.

After this many years, I still really like how the beginning of this piece turned out.

“Where the toxins grow,” the contextual sidebar that originally accompanied the story, is included at the end.

Originally published Sept. 4, 2005 in The Daily Reflector | (c) 2005 Cox Newspapers, Inc.

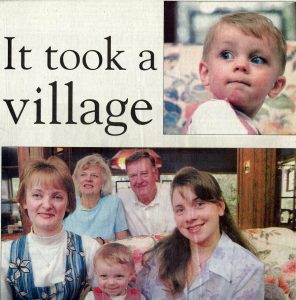

It took a village

Greenville (N.C.) embraces ‘Chernobyl baby,’ mending his heart, changing its own

This is a story about hearts.

Big hearts and small ones. Hearts on sleeves. Tiny silver ones on serpentine chains. Plucked heartstrings and poisoned heartlands. Hearts broken, mended, stopped. Hearts started again.

Because mostly, this is the story of a gravely ill little boy who, with the aid of all the king’s horses and all the king’s men, had his failing heart put back together again.

THE WAITING ROOM, June 21, pediatric intensive care unit, Pitt County Memorial Hospital. Faces drawn with worry. Eyes unable not to keep from fixing on the door where the doctor will, in the next few hours, enter, hopefully bearing happy news. Or if he enters sooner, the world could possibly break in two.

When Ted Koutlas steps into the room following his surgery on Ilya Barabanau, the 15-month-old Belarusian boy with the hole-riddled heart, he is two hours early. But no one screams and no one weeps. Success shows in the cardiac doctor’s face. The child’s mother can tell, even if she can’t understand Koutlas’ light-hearted words.

“He’s fixed,” the surgeon says.

This once-broken little boy’s story is one of perilous twists and turns, unlikely chances and seemingly unlikelier outcomes. Call his even being alive now a series of overlapping coincidences, a gift of fate. Or call it the touch of God, as do many of the people who played a part in getting this beautiful child from an impoverished land half a world away to a state-of-the-art medical facility in a former tobacco town. Because if the stars had not aligned just so, there would be no fairy-tale happy ending here.

Cut to not even three weeks after Ilya has been cracked open to defuse the leaking time bomb in his chest. Cheerios are strewn across the couch and floor of Dick and Alice Evans’ immaculate Lynndale home. A couple of tiny whole-grain O’s remain clenched in the boy’s rosy fists.

Ilya isn’t family to the couple, not by blood. They had only met their little houseguest days before his operation. Yet the two of them beam like doting grandparents at the robust, bounding boy now leaving a path of cereal in his wake.

THE REV. CAROL Goehring knew the right guy the moment she got the letter. Someone at a Rocky Mount church was trying to track down a local dentist to go on a mission trip to Belarus.

Dick Evans, she thought.

“Because he’s retired, because he still practices, and because he, I think, has a big heart,” explains Goehring, co-pastor at Jarvis Memorial United Methodist Church with her husband, David. “We have other dentists in the congregation, but he’s the one I thought of.”

Goehring held onto the letter until she next saw Evans about a week later. She pressed the request into his hands.

Evans had retired from private dental practice in 2000, after more than 30 years. He and his wife had been discussing doing some form of a mission trip together for a while. Now here was this.

“One thing led to another,” Evans says.

But where the heck was Belarus?

Jim Privitt, a retired dentist from Kinston, had also been selected for the mission. He and Evans had been friends for years, part of the same Bible study group.

The trip was being coordinated through another old friend, Sam Pettaway at First Baptist Church in Rocky Mount, in conjunction with the American Belarusian Relief Organization.

The ABRO program brings children to the United States for part of each summer, to get them out of the radiation, meet their medical and dental needs, and provide a temporary safe environment. Many of the same kids return year after year.

The mission group of about 10 — Alice Evans went as her husband’s dental assistant — arrived in Gomel, Belarus, in January 2003, “the temperature hovering somewhere between zero and 15 below,” Dick Evans recalls.

Gomel was one of the hardest-hit regions of Belarus during the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986.

A woman named Valeryia “Lera” Navumenka, from Belarus’ capital city of Minsk, was to serve as the Evans couple’s translator.

“She took my wife and I under her wing,” Dick Evans says warmly. “She was my mouth in Belarus; I could do no dentistry without her. She sat with me every day, hours at the chair, helping.”

Dick and Alice Evans returned last year to provide dentistry services a second time, with Navumenka again serving as interpreter. By then, a strong bond had already been formed between the American couple and the young Belarusian woman.

“She’s become like family to my wife and I,” Dick Evans says.

Last October, the Evanses persuaded Navumenka to use some of their frequent-flyer miles to come visit them in Greenville.

“We went to Disney World,” the Belarusian woman recalls with a smile.

But not long after she arrived at the Evans home, the couple noticed she seemed increasingly preoccupied. Navumenka was frequently on the family’s computer, e-mailing home. They finally asked her what was troubling her.

She told them about her best friend, Maryna. And she told them about a little boy named Ilya.

And Dick and Alice Evans knew immediately that they had to help.

ILYA’S FIRST SIGNS of trouble showed up when he was about 6 weeks old. A heart murmur. Further examination only turned up more bad news.

Holes in the heart.

Typically, the vital organ’s two atria are distinct from its two ventricles. “For most of us, there is no commonality between the chambers of the heart,” explained Dr. Dennis Steed, who coordinated much of the effort to get Ilya treated in Greenville.

But in the little boy’s case, there was no distinction, a congenital flaw. Ilya’s particular condition, known as a partial atrioventricular septal defect, is not uncommon to children born with Down’s syndrome, but much rarer in children without.

In layman’s terms, the boy had a big “hole” in the center of his heart, causing it to beat much harder than it should.

In Belarus, the condition is sometimes known as “Chernobyl heart,” and is commonly held to be the result of radiation exposure, though there is no scientific evidence to support that claim.

But it’s hard not to speculate.

“Being as this (condition) is much less common with kids who don’t have Down’s syndrome, you can certainly wonder if (Ilya) would have had the same risk if he hadn’t been exposed to radiation,” Steed says.

Surgery can typically address the defect, regardless of its cause.

“With a lot of these (holes), you can fix them and then they’re done,” Steed explains. “That’s the biggest plus of kids’ heart disease.”

But Ilya’s home country, impoverished and politically precarious, is profoundly lacking in medical resources. The HBO documentary “Chernobyl Heart” reports that in this country of 10 million, the average Belarusian doctor makes around $100 a month; the standard “patch” for repairing a single hole in the heart is $300.

The film further asserts that about 7,000 children are expected to die within two to five years of being added to the waiting list for crucial cardiac surgery.

Ilya was on that list, and had been since his condition was discovered weeks after he was born.

But the septal defect itself constituted no immediate medical emergency.

“That aspect (alone) would have taken a long time to have gotten him in trouble,” Steed says.

The murmur complicated matters; Ilya had a severely leaking heart valve.

His mother, Maryna Baranava, took the boy to a hospital in Krakow, Poland, considered the boy’s best option for care.

“They had heard that this hospital was one of the best in Europe,” Navumenka explains for her friend. “That was the best possible medical treatment they could get.”

An echocardiogram was done, and doctors there agreed to do the surgery — but not until the boy had gotten a little older.

They also told Baranava that Ilya would likely require two or three surgeries in all. But for now, the condition wasn’t critical.

It would become much more so in the coming months.

Upon Ilya’s arrival in Greenville, his health had taken a turn for the worse. The presurgery echocardiogram at Pitt Memorial changed the whole equation, and quickly. The boy had developed pulmonary hypertension, and an enlarged heart.

“That at some point would have become irreversible,” Steed says. “The longer we would have waited, his risk would have accelerated.

“He could have run into serious trouble by winter.”

THE LEGWORK TO get the boy over here started in earnest this past spring.

Navumenka translated Ilya’s medical records into English, and arranged for all his earlier electrocardiograms to be videotaped and sent to Dick Evans. The retired dentist then shared Ilya’s story with Dr. Tom Irons at East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine.

“He said, ‘We need to fix that little boy,’” Evans recalls.

Irons suggested that his old friend go tell the same story to Dennis Steed – who, as it turns out, was one of Evans’ many former dental patients here in town.

Steed jumped right in. He would arrange for the necessary physicians and support team if Evans could get the hospital to sign on.

So Evans went to see Pitt Memorial CEO David McRae, a friend for many years. McRae then put Ilya’s story to the hospital’s chief administrative officer, Steve Lawler, another of Evans’ former dental patients.

“Within five minutes (Lawler) said to me, ‘We’ll do it. We’ll take care of him.’”

But there was still one more obstacle, much less obvious, but crucial: If Navumenka was ever out of Dick Evans’ sight, there would be no communicating with the boy’s mother, who speaks no English.

So Evans went to see One Source Communications owner Mike Aman about renting some cell phones, to serve kind of like walkie-talkies. Aman wouldn’t let Evans pay for them.

“He said, ‘Don’t deny me the privilege of helping these people.’

“People just came out of the woodwork to offer their services to help this little fella,” Dick says. “It’s endless what people have done.”

WITH MEDICAL ARRANGEMENTS completed in Greenville, the boy’s mother and her best friend set out with Ilya from Minsk, by car, driving 12 hours to Warsaw, Poland.

Ilya’s condition was by then visibly worsening; he had begun to look weak. His mother was afraid to put him on a long plane flight, but was far more frightened of staying put. Not taking the chance could leave her son as one more sad Belarus statistic.

“He did very well on the flight,” Navumenka says. “Myrna asked many people to pray, and she prayed herself.”

Roughly 24 hours after boarding the Polish plane, the trio arrived in Raleigh, on June 15.

Several eastern North Carolinians chipped in their frequent-flyer miles to get the two women here. A separate ticket was bought for the boy.

But as the Belarusian trio departed the plane in Dublin to proceed to their connecting flight to New York City, everything came to a halt. Navumenka had gotten through customs, but Baranava was stopped. Could they please see her visa?

In all the planning to get the trio here, no one had thought about an Irish visa, since the three were only changing planes in Dublin, nothing more.

They couldn’t enter the country even to leave it.

Navumenka explained their situation. They were traveling together. They weren’t staying in Ireland. Please, she said.

“You cannot leave this woman and a baby here in a strange country,” she told the man.

The customs agent buckled, though warning them that, minus a visa, they’d be refused entry on the way back.

“They were so nice,” Navumenka says.

JUNE 21, 1:30 A.M., the final hours before the intricately orchestrated surgery. Ilya’s mother discovers her son on fire with fever. But presurgical requirements forbid the boy to be given any liquid, medication or otherwise. And yet the doctors are unlikely to operate if Ilya has a fever …

It’s an emergency. “The window of opportunity is only from here to here,” Dick Evans says, illustrating the tiny space with his hands.

“I said: All I know we can do is pray for him.’”

Navumenka told Evans that she and Ilya’s mother had already laid hands on the boy and prayed for him.

“I said, ‘Well, as in touch as you two gals are, I’ll just say amen and we’ll go back to bed.’”

At 4 a.m., the house roused itself. Time to go to the hospital. They went in to check Ilya.

No more fever.

Dennis Steed had told Evans going into the operation that the little boy’s problems were likely too severe to fix with a single surgery, which meant somehow getting Ilya back here again even as Belarus’ totalitarian government was making foreign travel increasingly difficult, and preventing incoming humanitarian aid (In April, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice referred to Belarus under President Alexander Lukashenko as “the last true dictatorship in Europe”). The Greenville doctors expected they were only buying the boy some time.

Ilya was expected to be in that first surgery for five or six hours; it took three.

“He sailed through it,” Steed says.

And seemed to heal as if by magic.

“When they told us in two days after surgery that he could go home, Myrna thought the surgeon was joking,” Navumenka says. “We couldn’t believe that.”

A tiny heart murmur still remains, but Koutlas and Steed think it’s safe (many children have mild heart murmurs). And Koutlas believes there is about a 90 percent chance the child will never need another surgery.

Ilya, indeed, was fixed.

A GRAPH OF the outpouring of support on behalf of the Belarusian boy would resemble nothing so much as a tree, with Lera Navumenka as its roots.

“She’s given up five weeks of her life and her job to be able to come over here and do this,” Dick Evans says. “She is a beautiful, sweet, wonderful person. She is the queen of this whole deal, the glue that holds it together.”

When Evans looks at Navumenka, his eyes often go cloudy. She is, by any estimation, a remarkable person.

In the right light, a raised pink scar is evident on the young woman’s neck. Evidence of one of her own surgeries — there have been four — for thyroid cancer.

The trunk of the tree would be Dick Evans himself, though he characteristically tries to forward all credit to others. From there, the branches go in sundry different directions.

Doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, congressional aids, fellow dentists, even a very enthusiastic postman – after a short time, talking to any of them starts to sound strikingly familiar: I had the easy part, they invariably say. Someone else did more.

In fact, many people did more.

Cribs, strollers and toys have turned up at the Evans house — gifts from Jarvis Memorial parishioners, often people that the couple barely even knew. And nearly every day, someone else brought over dinner cooked for the family and their guests.

“These people have been with us for five weeks,” Dick Evans says of the Belarusian trio. “That’s a lot of cookin’, a lot of feedin’.”

Eventually, all talk of helping, of community support, circles back around to take in the word “miracle.” The odds were against this happening, everyone says. But it did.

The boy’s mother, visibly overwhelmed by recent events, cannot convey her gratitude without her voice breaking repeatedly. Thank you, she says, to everyone, for giving me back my son.

She can only believe that it was all God’s will. A miracle.

“Ilya” translates as “Elijah,” a Biblical name. His parents thought even before he was born that he would be, like his father, who was not permitted to leave Belarus, a man of God.

THE BELARUSIAN TRIO left Greenville on July 19, bound for home, where there are still warnings against wild mushrooms and berries, which readily store radioactivity, and which many people pick and eat anyway. In Belarus, homemade jam constitutes a health threat.

Ilya’s home in the city of Mogilev is less than 20 miles from the radiation-saturated Exclusion Zone, where several hundred people have illegally returned to live after being evacuated following the Chernobyl disaster.

In “Chernobyl Heart,” one man tells interviewer Adi Roche, the founder of the Chernobyl Children’s Project, “To leave the motherland where you were born and raised, where your soul is connected to the earth — I would not want to. To move to a new place is difficult, especially in terms of a job in Belarus and abroad.” His daughter was at that moment facing surgery due to a congenital defect — the Chernobyl heart.

Myrna Baranava is vividly aware that she is taking her son back to a place commonly accepted as being among the most unhealthy on the planet.

“Da,” she says quietly. Yes.

When she and Navumenka departed the U.S., they wore silver necklaces bearing small Valentine’s hearts, each containing a tiny Christian cross. Gifts from one of the Evans’ three daughters, celebrating the two Belarusian women’s strength of faith, and a little boy’s fixed heart.

Irish visas, running $78 apiece, were secured for the return trip, supplied free of charge, from the embassy in New York City.

“So even Ireland’s been involved to take care of this baby,” Dick Evans says.

On the last Wednesday afternoon before their departure for home, Ilya was finally allowed to get his chest wet following surgery. So the Evanses took their three guests to Atlantic Beach. It was tough to say who enjoyed it more, Dick Evans says, the child or the two Belarusian women.

The couple, who have come to think of Navumenka like another daughter, have eight grandkids by their own girls.

Well, had, anyway.

Alice looks again at the trail of Cheerios on her living room floor. Smiling, she shakes her head.

“It’s nine now,” she says.

(SIDEBAR) Where the toxins grow

A Google search for the year 1986: The return of Halley’s Comet. The horrific Challenger explosion. The Mets winning the Series. Tom Cruise in “Top Gun.”

And tucked among the search results, receiving little more emphasis than the arrival of the first disposable camera, you’ll find what’s now considered the most deadly accident in human history.

Chernobyl.

On April 28, 1986, Geiger counters in Sweden started giving off frightening readings: Radioactive dust was being borne up from the south, from the northern part of the Ukraine, then under the rule of Soviet Russia. Excessive radiation levels would later be recorded as far away as Ireland, in one direction, and Alaska, in the other.

At the nuclear power plant in the village of Chernobyl 80 miles north of the Ukraine capital of Kiev, a superheated explosion two days prior had produced a plume of toxic particles that shot up a mile from earth. Before it ceased days later, about 190 tons of radioactive material and charred graphite were loosed into the air. People in the immediate vicinity were exposed to radiation levels 90 times higher than at the bombsite in Hiroshima.

While the cloud drifted across Europe, it rained down in an invisible blizzard atop the country that is now the Ukraine’s immediate neighbor to the north, the republic of Belarus.

More than 400,000 people would be evacuated from the worst-contaminated areas closest to the spewing reactor, and 2,000 villages razed. An estimated 600,000 conscriptees were brought in for cleanup efforts; 13,000 of them are, by the most extreme estimates, believed to have since died.

In the nearly two decades since, hundreds of evacuated residents, many of them elderly now, have illegally moved back into this zig-zaggy no man’s land, dubbed the “Exclusion Zone.” When interviewed, these refuseniks often say that if they could survive the very real Nazis and the equally real Soviets, then something invisible seems a paltry risk of killing them.

It’s part of the Russian-Slavic character, said Harold Stone, an assistant professor in ECU’s School of Industry and Technology, and a Fulbright Scholar to the Ukraine in 2002. The Slavs “depth of culture provides them with an anchor that allows them to withstand things that we can’t even understand.”

Stone has spent considerable time, both professionally and personally, in Eastern Europe, and owns a second home in the republic of Crimea, another former Soviet territory, to the south of the Ukraine.

“You talk about British stiff upper lip,” Stone said. “British stiff upper lip in my mind doesn’t compare to the siege of Moscow by Napoleon. It doesn’t compare to Stalingrad during World War II. It doesn’t compare to the worst days of Stalin.

“There is a heart of sorrow within the (Slavic) mind that is their greatest strength,” he said. “You have to think of that from the standpoint ofChernobyl.”

Some estimates put 99 percent of Belarus — once known as the “Soviet Breadbasket” for the agricultural bounty it produced — as being contaminated by radiation, based on international standards.

“I think that’s probably a bit of an exaggeration,” said Daniel Sprau, director of ECU’s environmental health sciences program, who’s done work with the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency. “Maybe not a bit, maybe a lot.

“Unquestionably, it was a disaster,” he added. “Things are contaminated. But I think what they’re finding now, outside of the human health factor, is that the Earth is rather resilient. Things don’t seem to be as bad from the gist of what I’ve seen as one might first have thought.”

Yet inside the rubbled Chernobyl plant, the bulk of the original radioactive material still remains, only marginally contained, as the shell of the building — the sarcophagus — slowly falls in on itself.

Many in the international scientific community have contended that “the next Chernobyl” could well be Chernobyl itself.

“You wouldn’t want the sarcophagus to fall in,” Sprau said mildly.

Very little about Chernobyl is not contested.

The controversy goes far beyond Soviets attempts to hide and then play down the catastrophe, and the subsequent failures of the international community — including the United States — to provide promised assistance. Questions now go much deeper.

The United Nations released a report in 2002 that suggested that many of the Chernobyl evacuations might have been premature — that resettlement had created worse problems, that reports of radiation-caused medical concerns were exaggerated. The World Nuclear Association has been among those to seize upon the report, playing down many of the once-accepted Chernobyl statistics in favor of the suggestion of international overreaction to the disaster, and of psychosomatic illness exceeding real health threats from radiation exposure.

Bolstered by this report, the Lukashenko-led Belarusian government has discontinued much of its subsidy program to people living within what had been officially regarded as the most affected areas.

Yet earlier this year, the National Academy of Sciences reported that even very low doses of radiation — repeated X-rays, for instance — pose a risk of cancer over a person’s lifetime.

But even that remains open to debate.

“There is actually some body of evidence to say that low doses of radiation may be good for you,” Daniel Sprau said. “It’s called hormesis.”

Not surprisingly, there is no widely accepted scientific evidence to support, or refute, the notion that radiation has created an ongoing, and unfixable, health crisis in Belarus.

Different sources report differing public-health threats.

Cham Dallas, an associate professor of toxicology at the University of Georgia, wrote last year that “to date, no significant increase in birth defects has been detected.” He likewise reported that the birth rate in southern Belarus has steadily declined since the Chernobyl accident.

“The women terminate pregnancies by abortion or decide against pregnancy due to a fear that is not scientifically substantiated,” he writes.

And yet doctors in Belarus point to now-packed hospitals. They say: Just look.

“Belarus cannot cope,” said Lera Navumenka, a translator to visiting health missionaries in Belarus who was visiting the U.S. recently. “So many people need medical treatment. Hospitals are overcrowded.

“There are a lot of cancer cases,” she said.

In the Gomel region, the part of Belarus closest to the Chernobyl site, thyroid cancer occurs with 10,000 times the frequency as it did before the 1986 disaster, according to the Academy Award-winning HBO documentary “Chernobyl Heart,” released in 2002. Navumenka herself has undergone four surgeries for the condition.

The infant-mortality rate in Belarus, contends Ireland’s Chernobyl Children’s Project, is 300 percent higher than in the rest of Europe. Low birth weight is increasingly common, as are gastrointestinal disorders, severe brain damage and obvious genetic abnormalities (children born with eyes on the sides of their heads, and with brains bulged from their skulls), along with other profound congenital defects.

But is it the radiation? Or is it something else entirely? If a definitive answer hasn’t arrived in the two decades since, there seems little hope the question will ever be resolved.

A two-day conference, “Chernobyl — Looking Back to Go Forwards: Toward a United Nations Consensus on the Effects of the Accident and the Future,” begins Wednesday in Vienna. Put on by the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency, it will assemble “hundreds of experts and government representatives from Ukraine, Russian Federation and Belarus” to discuss the after-effects of the 1986 reactor breach, according to the IAEA Web site.

ECU’s Daniel Sprau, who has done work with the pro-nuclear IAEA, describes the organization as “the watchdog for safeguards on nuclear power.” Sprau hopes to take a group of students and faculty to Chernobyl this spring, to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the radiation disaster. Members of his family may also make the trip.

He isn’t worried about potential health risks, he said.

“We’re only there for a day, and certainly there’s radiation exposure, but you get exposure here, in Greenville,” he said. “And I don’t take my family to places where I think they’ll be in jeopardy.”

<Page likes lost from original blogsite>