So there I was, stranded along a quiet country road littered with smashed cut-flowers, beneath a darkening sky, beside a field full of foraging cows. Later that same day, a twitchy kid would stick a loaded semiautomatic rifle in my face.

I’ve determined just now, via a quick consult with Google, which was not yet even the inkling of a thing on that bygone April day on that lonely rural byway, that I was stalled somewhere along the NR15, National Road 15, in the far northwest of Ireland. Not Northern Ireland, to be clear, though not terribly far from there, either.

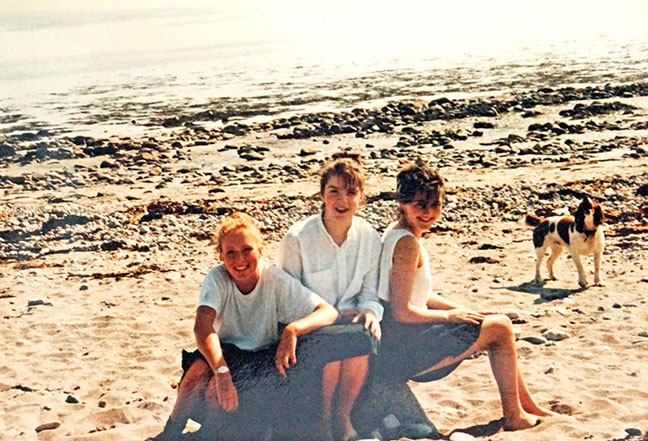

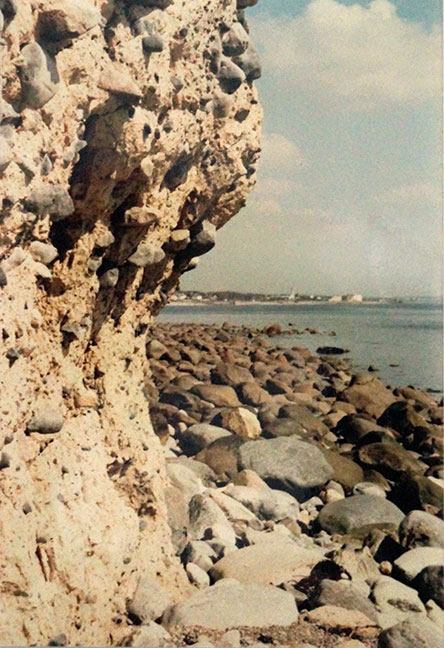

I’d been hitchhiking north-ish from, as best I can now recall, the west-coast town of Sligo, having come the day before through Galway where, as I gazed out from a rocky beach into that bay famous from Irish-expatriate song, a trio of teenage girls playing hooky had flirtatiously tossed pebbles at me.

Anyway, I’m pretty sure I was leaving from Sligo that day, and not actually from Galway. Or Clifden. Or maybe even Connemara. At some point around that same time, I had passed through all of them. This was, you see, more than 30 years ago. My memory can get a little dicey, even on yesterday.

The thing is, though, the cows. That field full of friendly cows.

Also, that kid with the big, ugly gun, sure; the thing has also got to be that kid with the gun. But even more than that, the 30 years. The thing here really is that 30 years.

I got it in my head in my late teens that it was a good thing to donate blood. This is a little startling in retrospect, being as it is absolutely correct, something I so infrequently was in those days.

I had yet to see true violence up close, the brutal human aftershocks of near or distant wars; the lives shattered in vehicle accidents orperversely American “peacetime” gun attacks; the hells of cancer and chemotherapy on a body. I just knew you were supposed to give blood, that’s all. You were doing your part. You were helping others.

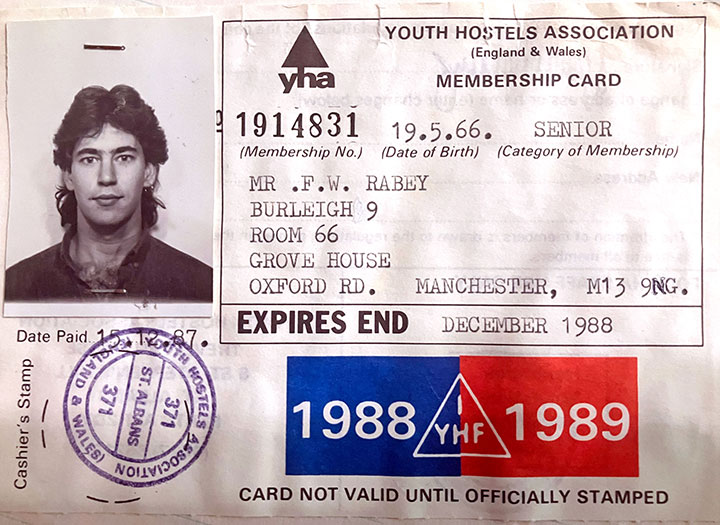

My first two years of college, at East Carolina University in hometown Greenville, N.C., I donated several times, and then for whatever now-unknown reason, promptly fell off the blood wagon after transferring to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The change in schools would allow me, however, through herculean academic and personal effort across two overloaded semesters of perpetual exhaustion, to spend my senior year, 1987-88, at the University of Manchester, in England, which would become among the single-most rewarding things I would ever do.

I didn’t attempt to donate blood again for quite some time after arriving back in the States. I was then, in so many ways, and for far more years than I’m comfortable admitting, adrift in the wilderness of my own life, awaiting some sign as to what the hell I should do with myself next.

I’ll tell you, if you like, that I have long since figured all of that out.

Back again, to that Irish road. That field. That ominous sky. Those fabulous cows.

I was beginning my third and final week rambling around Ireland, on foot and via thumb, toting a nearly 50-pound framed backpack containing, among my clothes and assorted gear, several hefty books for a couple of assignments due upon my return to Manchester following the spring break.

I’d caught a lift late that morning, presumably out of Sligo – or, y’know, Galway, or Clifden, or Connemara; clearly, geographic details are a little loosey-goosey here, memory, such as it is. On top of that, the journal I kept during my year abroad, re-discovered only recently, is mostly just overwrought emotional impressions and smatterings of appalling juvenile verse. Far too few details of my surroundings.

The ride, from wherever up-northish I was actually departing, was with a flower-delivery driver who told me he was going up toward Donegal, my own intended destination. The driver seemed a nice-enough guy, chatty, and truly delighted to have an American along for the trip.

The back of his delivery van had shelves to either side loaded with flower arrangements, many in the form of wreaths, perhaps bound to a funeral that same afternoon. The irony of this would hit me only much later, like a belated brick through a bygone shop window.

We traveled pleasantly for a while, into verdant open country and, while I didn’t know it at the time, through townlands with richly evocative names – Coolcholly, Ballincurry, Tullyhorky, Mollyroe. We met with increasingly little traffic and, finally, nothing but open space to all sides, much of it pasture for cattle.

At some point the driver’s conversation narrowed dramatically, to a very specific topic: the Troubles, the entrenched Northern Ireland conflict of car bombings and other bloody sectarian attacks led by paramilitary groups on both sides, Catholic and Protestant, the most notorious being the IRA, the Irish Republican Army.

International news back then routinely covered Belfast, the Northern Ireland capital, as a war zone.

This was the late 1980s, remember. Right in the thick of it, with another decade of madness before the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, which marked the official “end” of the ongoing violence. By then, more than 3,500 people, civilians and military and police, had been killed, and another 47,500-plus injured.

I was not a particularly bright young man. Though relatively sharp in the book sense, I suppose, I was a bit too convinced of my own worldliness, and too often displayed a bull-headed lack of sense you might more associate with, well, a moron, really. Nonetheless, I instinctively knew better than to jump in on this particular topic, taking any side at all. Hell, I didn’t, and honestly still don’t, have enough understanding of the subject to take a position on it anyway. I hadn’t endured the hell of it personally, or even lived, as the van driver had, in the long shadows of the two countries’ complicated border.

The guy hardly needed me to chime in regardless. Once he got going, I was simply a prop – a living prop – for his escalating fury.

I wish I could recount a few details from his wild ranting, which he frequently intercut with questions to me he never waited on to be answered. I can’t even say for certain now which side of the issue he was on. All I’ve been able to pull from my memory, for years now, is that he bought into some conspiracy theory about Northern Ireland and the Kennedys, John and Robert, that to this day I can find no information to help me understand, especially since the IRA itself didn’t come into existence until after both brothers were several years dead. Whatever the true gist of the driver’s grist, he’d made the mental jump that because I was American, and looked, as I had so often been told, like I was Irish myself, another young pilgrim visiting the ancestral homeland – a smattering of my DNA, on my mom’s side, is likely green, in fact – that I was open to buying whatever he was selling.

The truth is that after a certain point, I was no longer paying much attention to what he was saying. Because the whole time his anger was flaming-up, the van was also rapidly accelerating, even as his control over his driving was slipping dramatically; we were soon weaving all over that curvy road, running off onto the shoulder more than a couple of times. Too, he had become absolutely beet-red, his face and arms, even down into his hands, which he’d started pounding upon the steering wheel as he shouted; he was then doing nothing but shouting. If he didn’t kill or maim us by running the van once and for all off the road, his heart seemed likely to just explode.

I cannot begin to convey to you the level of this guy’s anger.

Jump forward almost 20 years. My local hospital, where I was also then employed as a media specialist, was hosting a blood drive. I knew I should take part, both for personal and work-related reasons, but when I sat down with a Red Cross representative to run through the pre-donation questionnaire, we got stuck at what struck me as an odd question:

Had I been in Great Britain between such-and-such dates?

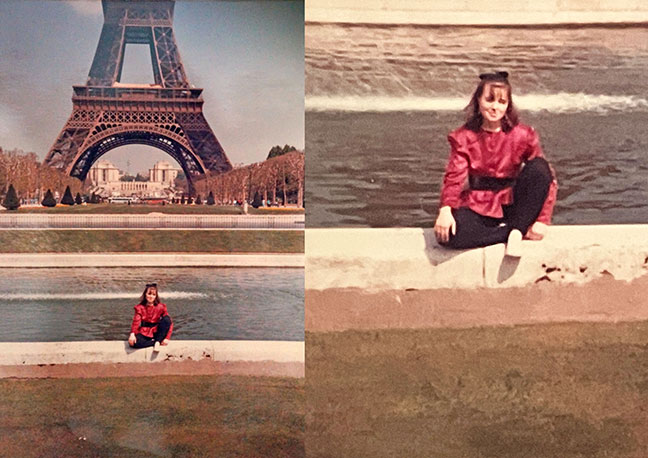

That time period included the year I lived in Manchester, and traveled across much of Great Britain, as well as into continental Europe, on the meagerest of funds. The same year I was stuck for hours on that quiet Irish road in what would become a wretched downpour, watching the then-retreating backs of amiable cows.

Come to find out that was also the time period when mad-cow disease – officially, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) – was making its deadly way through British cattle. Now, I certainly ate no shortage of beef when I lived over there; in England then, good luck finding a dish without it, often with everything boiled to the point of tasting like absolutely nothing. If only I’d discovered the wonders of Indian food early on, and not in the final month before I left …

There was, when I showed up to donate that afternoon in the late 2000s, no way to tell, in the absence of actual BSE symptoms, if a potential donor was a carrier of the fatal brain disease from his or her blood. So, much to my dismayed surprise, the Red Cross was compelled to turn me away.

I did ask when I might be able to give blood again. They didn’t know. There was a chance, I was told, that I would never be able to. I should check back periodically to see if there was any new information.

Which I did several times over the next few years, at blood drives hosted by other organizations, including my now-current employer. I was turned away each new time, always apologetically, because people willing to give blood are but a tiny percentage of the total human population, even as there’s never enough standing blood supply to keep all of us in potential need of it alive.

At some point in the van’s increasingly chaotic swerving, one of its back doors popped open. Flowers started falling out, at first just a few at a time. At first.

I had already begun trying to shout through the driver’s blinding vitriol when the second door came unlatched; both were soon flapping wildly as we careened dangerously forward. Whole arrangements were by then tumbling from shelves to floor, one after another, bouncing out the open doors and exploding like petaled bombs across the tarmac.

Try as I might, I couldn’t get anything to register with the driver: Your back doors are open! Your flowers are falling out! You’re losing everything!

I recall somewhere along in there furiously shaking his closest shoulder. Something, maybe that, finally got through to him. His whole expression changed in an instant, and he brought the van to a hard halt. Then he just sat there, gripping the wheel with both blood-red hands, saying nothing.

I remember glancing toward the back: The van was pretty much empty; the guy had indeed lost everything. One of the doors was hanging funny as well.

“I can help you try to pick this stuff up,” I recall saying. It was a pointless offer; the fallen arrangements, the ones we could still even see, were clearly ruined. I just knew he would likely lose his job over this.

The driver shook his head. The flowers, amazingly enough, were not the thing most on his mind.

“Let me get you to Donegal,” he said, or something close to that. “I promise to stay calm. I’m so very sorry. Please let me just get you where you’re going. Please.”

Um, no.

“I’m fine,” I responded. “Really. I’m just gonna hop out here, OK? Someone will be along soon enough, I’m sure.”

Well, a great, big oops on that one.

After I’d climbed out with my pack, the driver turned from me to look at the road. He never even got out to try fix his doors, but just drove off, considerably more slowly, one door still flapping lightly against the back of the van.

Despite the incredible danger he’d put us in, I nonetheless felt horrible for him. Never in my life have I seen another person so totally consumed by shame. To this day, a small part of me feels I should have let him take me the rest of the way to Donegal.

A time frame did finally emerge in the 2010s as to when I might have a real opportunity to donate blood again.

So here’s where that 30 years comes into all of this: I could maybe donate again in 30 years from my time in England.

It was assumed that if a person potentially exposed to BSE had not become sick in the subsequent three decades, that he or she was in the clear – though it had honestly never occurred to me I might be otherwise. Hell, I didn’t even know about the disease until long after I was back home in the States, certainly not while I was scarfing down yet another damn shepherd’s pie in yet another English pub, much less standing next to a field of inquisitive Irish cows.

The 30-year timeframe was still speculation, though; the Red Cross had no official policy set beyond wait-and-see.

By the time it hit me that 30 years had elapsed and I could at last maybe donate again, COVID had hit. In the meantime, I could find no updated info to suggest my attempt would go in any way other than it had before. It seemed too much of a bad gamble, putting myself or others at heightened risk of yet another rotten disease for the great likelihood of yet another donation fail.

Which made it all too easy to let the subject slip off my radar once again.

My mind has returned to that lonely Irish road surprisingly often over the intervening years.

To one side, that unbroken expanse of green, stretching as far as the eye could see; to the other, that field behind the slatted-wood fence, and some ways behind it, that sizable group of cows wandering around, faces to the ground, enjoying a little afternoon nosh, no more aware than I of that fatal disease that could potentially soon befall them, or me.

There was nary a hint of anyone else anywhere near, and that rain-saturated sky was increasingly making no bones about its intentions.

At first I simply stood beside the road, thumb at the ready. Then, after so much nothing at all, I set to pacing. I even wandered back a ways, to look at all the broken flowers zigzagging past my sight along the otherwise-empty asphalt. Why I took no photos of this, I do not know.

Finally, I moved my pack back to up along the fence, so I could have something to lean against.

When I’m bored, I will often sing. I’ll start out with snatches of actual songs, then invariably begin making up stuff that fits my trembly baritone.

So I started in with the singing, propped against that fence, trying not to focus on the downpour to come, and to no doubt change my own tune toot sweet.

I happened about then to glance behind me. That whole host of cows had quietly ambled up to directly behind me, right there at the fence. Several of their intent brown faces were just a few feet from my own.

It was jarring at first, and then I thought it was simply wonderful. Because it had to have been my singing, right? So I stopped – and soon enough, all those cows wandered back away.

The only thing to do then, clearly, was to start in singing again. And right back they all came, to a cow, standing once more just beyond the fence, watching, and listening, some of them close enough to touch. I didn’t, though, as charming as all of this struck me. Because I don’t know for cows.

This fun little act kept me occupied for a fair bit. I mean, I always thought I sang OK, but then here were these cows, just rapt. I clearly had a future in improvisational farm-field entertainment …

And then.

And then the sky said it’s time, bub. The rain came, and holy hell, that rain.

I promptly stopped singing, because, well. The cows again wandered away, this time for good – maybe they had a nice, dry place nearby?

Whatever joy I’d found in any of this, no more. Little compares to the futility of being utterly alone in a foreign country, stranded in a cold-ass downpour, with absolutely nowhere to go.

Meanwhile, off in the distance, your former fan club is already retreating from view.

Fast-forward, to late last year, and my coming across one of the many online Red Cross notifications about the constant need for blood, and it hit me, out of the blue:

Wait, 30 years was five years ago. Maybe I really can finally do this?

I punched in a few things to Google, always now that fucking Google: mad-cow disease, giving blood, 30 years, England.

I got quick results. The Red Cross, as it turns out, had just officially declared that, yes, after 30 years with no BSE symptoms, a person was again eligible to donate blood.

I promptly made an appointment at the local office, for a day late last November. I confess to being extremely excited to have someone jab a spike into my arm and tap me like a human sugar maple. I was pretty wound up when I arrived at my Friday-morning appointment.

Because this was, in short, something I could do, a thing I could accomplish, to be broadly useful, especially since my current employer, a community-health nonprofit, had bumped me down to part-time last spring, due to budgetary shortfalls befalling many smaller hospital systems like my agency’s own primary business partner. It had become increasingly clear to me, and to my ever-supportive spouse, that I needed some new outlet where I could feel I was contributing something valuable to others.

So I got checked-in on that scheduled-donation morning, having already declared through the Red Cross app that, among other things, I’ve never been treated for AIDS; was not an IV-drug user; had not had sex with multiple partners in so many months, or sex for money, ever; wasn’t pregnant; didn’t have hepatitis; hadn’t taken aspirin in so many days ….

I did all of this, and after the Red Cross worker had punched in the additional info she needed, and even after she had completed a finger-stick on me to determine my hemoglobin level was acceptable, I was … once again apologetically turned away.

Turns out the Red Cross main office had to pre-clear me to give blood. I called their number later that same day, and was told that anyone who had been declared ineligible due to possible BSE exposure had to be individually assessed for blood donation after their own 30 years had elapsed. This obviously would have been nice info to have had prior to my going through the rigmarole of showing up and declaring my aspirin-free monogamy. But hell, I was finally on the verge of actually addressing what had quickly become my new obsession.

Too many of us on this goddamn planet. Too much to go wrong. Too little blood to help fix it. Too long not doing my own part.

It had stopped raining when a pickup truck – one of those short-bed models always more popular in Europe than in the U.S. – pulled over beside me along that spongy Irish roadside. By then it was late in the day, almost dusk, and the rain had cooled things down considerably.

The driver commented that I was in a helluva place to get a lift, something that maybe should have given him pause – I mean, what’s up with this foreign kid that someone would drop him in the middle of freaking nowhere? Thankfully, it hadn’t.

He was going right by Donegal; he lived just north of there. He mentioned needing to pop across into Northern Ireland to get petrol, which was cheaper over there; the outskirts of Donegal stretched almost to the border. Would I mind taking a little detour?

After I’d been stuck along that unfrequented stretch of road for hours, increasingly convinced I would be spending a damp, frigid night there? Hell no, I wouldn’t mind!

“Not at all,” I said.

In truth, I was also stoked at the prospect of crossing into Northern Ireland, even if it was just for me to sit in a car while someone else pumped gas.

“Hop in,” the driver said.

He was a fantastic guy. I remember this more from his general demeanor than anything specific about our conversation, which is almost entirely lost to me now; my journal mentions only that he worked as an agricultural inspector, and that we talked a bit about religion, which seems a potentially problematic topic for us to have undertaken in that highly charged section of Irish geography. I also shared with him what had transpired earlier to land me at my unlikely location. I may even have shared the cow bit, because I just loved that part, even then.

He was highly apologetic about how my last ride had ended, but introduced a small caveat, not so much in the earlier driver’s defense, but as partial explanation, a message he would repeat more than once before we parted ways:

Everyone this close to the border has some kind of a stake in the bloody human mess on the other side. Some have family over there. Some work in one place and live in the other. Many personally know people there who have been killed or wounded.

Inquiring of my plans, he suggested a bed and breakfast in Donegal, cozy and reasonably priced. It had a bar downstairs; I’m certain I had mentioned wanting a drink.

When we finally arrived at the border, it struck me as looking a lot like an interstate toll plaza here at home. Since having traveled on a family-heritage trip in 1997 across the Slovak border into the Ukraine, not but a few years after the USSR collapse, it now registers more to me as a fortified military roadblock, which it actually was.

We waited in a short line of cars to be cleared to go over. The driver noted that they were pretty touchy at the border, but as he was a regular crossing there, and I was an American, it should be nothing.

When we got up to the front, an armed, uniformed guard checked the border-crossing decal on the truck window, and he and the driver exchanged pleasantries. At some point the officer asked about me. Then things went south.

Another guy in uniform, with yet another semiautomatic rifle, came over to my side of the truck. I swear he looked to have been maybe 14, with terrible acne and a nervous expression you really don’t want to see on someone holding such an emphatic instrument of harm. I rolled down my window to speak to him, and he promptly shoved the barrel of his gun to within about an inch of my face, demanding to see my passport.

As bad luck would have it, I couldn’t at first place my hands on the damn thing. In the interim, that gun did not move. The driver kept telling me to stay calm, that it was gonna be fine.

It ultimately was. The kid took out a flashlight, peering down at my belatedly located passport for what seemed an incredibly long time, then abruptly handing it back to me. He didn’t say another word. He and his gun simply walked away.

I waited in the car, a ball of adrenalized energy, while the driver filled his tank. Then he turned us around, taking us back across the border the other way.

Once again, he felt compelled to apologize; he hadn’t expected that ugliness with the young guard any more than I had.

I don’t remember talking much more until we reached the B&B in Donegal. Even now, I can’t really imagine what I could have had to say.

On the phone with the Red Cross rep, to get individually approved to give blood, I promptly made another appointment, for about two weeks out. During the interim, I received a confirmation email: Go get ’em, tiger.

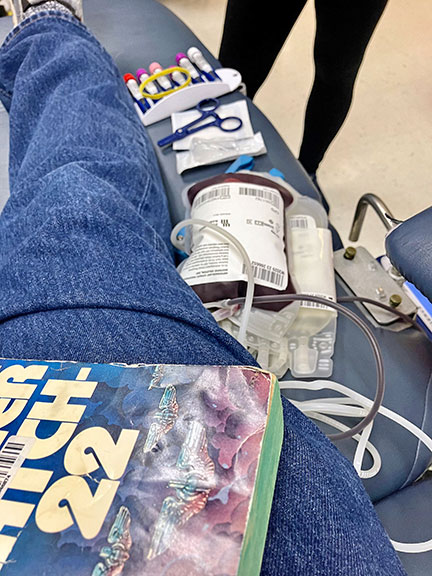

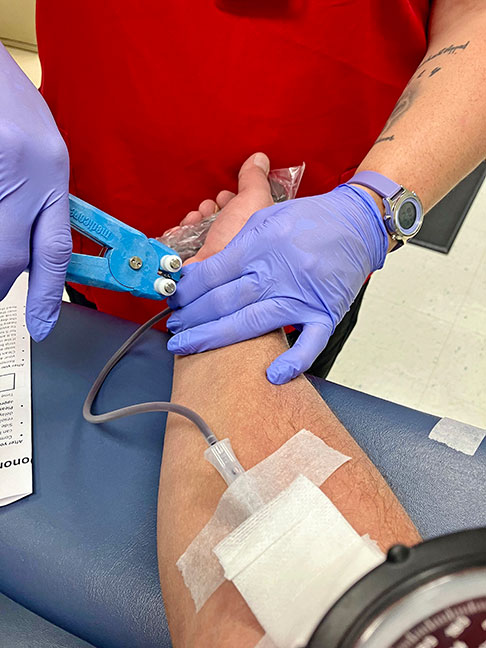

I showed up for that new appointment, redeclaring all the things I had declared before and … they took my blood.

More than 30 years since I’d last successfully donated, and they finally took my fucking blood.

Spike in arm. Blood drained into bag. It was a far quicker process than I had remembered from all those many years ago. Once completed, the full bag of my former blood sat beside me on the donation chair, plump like some miniature pillow.

“That’s your blood baby,” the phlebotomist informed me. “That’s what we call it, anyway.”

Some people have negative reactions to different parts of the donation process, from the alcohol solution used to clean your skin to the immediate diminishment of your body’s overall blood volume. Yet yours truly, who so often has unpleasant, often quite awful, side-effects, to damn near any alteration in his biochemistry, soared right through. No issues. Not a one.

While I was there donating that morning, there were also these old guys (OK, older-than-me guys) toward the back of the room, giving what I assumed was blood as well, except their whole setup was different. They had IVs running into both arms. They had on large headphones. One guy, covered in a blanket, appeared to be asleep.

Turns out they weren’t giving whole blood as I just had, but were instead donating platelets, a process that could take between two and three hours. They were watching movies on Netflix – and apparently sometimes nodding off to them – while they waited through the lengthy procedure, which involved extracting blood into a machine that rapidly spins the lifesaving fluid to extract the platelets before pumping the newly platelet-free blood back into the donor.

Platelets, I learned, along with plasma, were vitally important to people with cancer undergoing the brutal rigors of chemotherapy. I nearly lost one of my beloved sisters to the disease nearly two decades back, and then, a little more than a year ago, that same sister’s remarkable wife, whom I profoundly adored, succumbed to a different type of it after a prolonged and incredible fight.

I made a mental note: platelets.

The pre-warmed blanket, I was told, was because the anticoagulant solution used in the extraction process could make a donor feel cold, really deep-down cold.

The nice Irish bloke who’d rescued me from the middle of nowhere pulled us up directly in front of the B&B he’d mentioned. I thanked him warmly, and not just for the ride. I was already weirdly grateful for the unsettling episode at the border, because, wow, just wow. He nonetheless repeated how sorry he was about it yet again – that I, as a visitor to his country, had to experience something like that.

Before I got out, he offered me some parting advice: Enjoy your time here, fully. But tread lightly, if you can.

I got checked in, walking past the cozy on-site pub to the right of some stairs, and then up those stairs to a room both comfy and overly large for my needs. It had gotten quite chilly late in the day, so I turned on the room radiator, hanging my still-damp clothes on furniture beside it; the stuff in my pack, inside plastic bags, was all still dry. I took a shower, put on fresh clothes and then dragged out my books, vowing to work shortly on what I had mostly avoided for the majority of my trip. I would first just pop down to the pub, for a Guinness, because, Ireland, and my time there was winding down.

Guinness. Ireland. It was required, that’s all.

Not to mention I’d risked being killed earlier by an enraged flower-delivery man, while an anxious teen had much more recently stuck a loaded gun into my face.

Two ideas to be kept at great remove from one another: a lack of moderation, and a desire to make up for lost time. I decided after my first donation in more than 30 years – 30 years! – to give as often as I now could manage it, whether whole blood, platelets or plasma.

Thirty years of not doing what I felt was my part is a lot of time to cover.

Donegal, that same day, around 7 p.m.

I had just bellied up to the handsome polished-wood bar, where a few locals were doing their Guinness best. After ordering my own draft, and while waiting on the traditional double-step pour, I found myself drawn into chatting with the dapper gentleman immediately to my left; he’d heard my American accent, which was, at least back then, candy for conversation to Irish ears. Soon after, the gent to his left joined in with us as well.

I had barely started in on my beer – there’s nothing like a Guinness on draft in Ireland, nothing – when my new friends took my Americanness under their ideological wings.

We were no more than 25 kilometers/15 miles from the Northern Ireland border.

Tread lightly, if you can.

The two men, older gents, a bit older even than I am now, were exceedingly pleasant. Longtime friends, they were nonetheless on opposite sides on the issue of Irish independence versus fealty to Britain, and the bloody, bloody violence so close to home. They began politely discussing the subject, clearly not for anything close to the first time, though this time, they both had an audience who professed no stake in the equation. So it was ostensibly for my benefit, each explaining what I maybe didn’t know …

What happened next bewilders me to this day.

Whenever one of my new companions felt he’d scored a point against the other, he would turn to the bartender and say: Pour the young American another!

Understand that I truly stayed out of this, entirely. I sat there, trying to nurse my solitary beer, wondering by then why the hell I had come downstairs in the first place. Once again, I was little more than a human prop.

Before I’d put an end to this bizarre one-upsmanship, there were, no lie, six new pints of Guinness, wonderful Guinness, lined up in front of me to drink. I had barely even finished my first, the only one I had actually ordered.

Let me go on record saying that six Guinness, and I’m under the table – and likely hurling my guts up while I’m down there. Ah, we wimpy Americans.

But sitting there, I honestly didn’t see this ridiculous cycle ending with these two friends. What, were there going to be 20 pints awaiting me before it was over?

The old guys were absolutely shocked when I said I couldn’t stay to drink the pints they’d gotten for me, that I had to get upstairs to do some work. I told them how grateful I was for their generosity, and asked them to please enjoy those beers for themselves. It was the best I could muster, and I felt lousy for doing so but, seriously, what the hell?

I seem to recall one of them paying even for my own drink as well.

I think I may have worked for maybe an hour when I got back upstairs before just giving up on the day, that utterly ridiculous day tinged at both ends with dramatic suggestions of violence, and going to bed.

I’ve given blood several times since that first time again last November, and platelets several times more; you can donate platelets more often than whole blood. Once I even did platelets and plasma, figuring, yay, a twofer, help more needy people in a single go! That particular donation finally flattened me with after-effects, leaving me wrung-out and light-headed, useless for nearly the next 48 hours. I plan to mostly stick with whole blood and platelets from here forward.

That said, at one recent platelets visit, the newly trained Red Cross staffer couldn’t find a vein in one arm, and then was a bit off the mark on the other, such that the IV kept having to be re-adjusted, quite painfully. Before it was over, every employee had come up to try to assist, and I left that morning, after more than four hours of bloodletting and replacement, with five new holes in me. I felt fluish the whole rest of the day.

I’ve already given platelets again since then, and it went fine, though at my most recent visit, as bad luck would have it, I was paired anew with that same Red Cross worker who had gotten so fouled up two visits prior. She promptly failed again, on both arms. This time, I left with yet another five new holes in me, but unable to donate anything.

No matter. Individual instances of defeat are little match for true obsession. I will continue to do what I can, whenever I can.

See, I’m not sure I believe that we, as a species, can save ourselves from ourselves, much less this world we seem so hell-bent on destroying. And yet … there are so many good among us, so much human wheat mixed in with the toxic chaff.

I fundamentally believe, my festering cynicism be damned, that we have to count on that, the goodness, and goodness often needs some propping up, to find its footing along difficult paths. It needs a little juice, you might say. Perhaps a little fresh blood.

I woke up in a terrible funk that next morning in the Donegal B&B. I can’t blame it on the alcohol; I’d had exceedingly little to drink.

Everything just seemed so flawed to me. So much anger, rubbing perpetually against itself, igniting in often startling conflagrations.

This was a number of years before I would fully realize how being witness, sometimes even tangentially, to flagrant examples of suffering, human or animal, can simply destroy me, for days, weeks, even months on end. All I knew right then is everything felt horribly wrong.

The night before I had planned on heading back east across the country that very next morning. Instead, for no reason I now can remember, or that I wrote down back then, I instead pressed a bit further west along the coast, to the old fishing village of Killybegs, where I wandered the docks under the romantic delusion I might drum up a day’s work, had a drink or two later in a local pub, and then fitfully slept the rest of the night away.

The following morning, I re-hoisted my weighty pack and again stuck out my thumb, bound east for Dublin. I recall it taking a few rides to finally get there, though I can’t now pull up a single driver’s face or travel experience.

In Dublin, a city I adore, I found the youth hostel I’d stayed at when I’d arrived in Ireland weeks before; I’d already decided I would be on the ferry back to England that next day. My time before my final academic session was almost up. So what the hell, put a bullet in it, I figured.

Given my recent experiences, kind of a lousy expression to end that thought on, I suppose. But there you go.

Late that afternoon in the Dublin hostel, I met a woman of about my own age, Sarah, from Northern Ireland, one of those rare human gems from whom we are sometimes blessed to catch a stray fleck or two of sparkle and shine. Taken from my journal, about her:

So understanding, so gentle, funny, passionate, sincere … . She shouldn’t be real.

She was also mighty damn pretty.

Sarah described herself to me as an unlicensed social worker in her hometown Belfast, working with kids there who had lost family to the violence. She was in Dublin on holiday, heading home the next morning.

In that one night we spent together, mostly talking on and on in the hostel kitchen, I do believe I may have fallen in love with her. Beyond that, I’ll never now kiss and tell.

She called me Frankie, only Frankie; I had so hated that nickname as a kid – but then? Ah. I remember even now her small hand on my cheek.

After I shared my Donegal story with her, she so wanted me to see the Belfast she knew, the points in between all the pain. Too, she wanted to take me up to Giant’s Causeway, a place I had always hoped to visit, knowing of it since my teens from, of all places, a Led Zeppelin album cover.

I swear she could somehow see it in me, the thing I didn’t even know yet was so fundamentally broken. Maybe spending your whole life straddling a fault line makes you recognize cracks in all that’s around you.

I promised her that next morning, both of us still awake from the night before and unhappily having to depart one another, each for our separate destinations, that I would somehow return to Ireland, for us to take that trip, and I didn’t know whatever else.

But I never did. And whatever else never happened.

We stayed in touch by mail for several years. At some point, Sarah came to the States, the Boston area, becoming involved with a guy who would go on to treat her badly, really badly. She was able to forgive it, she wrote me.

I cannot help wondering, as I see all this now typed in front of me, if that boyfriend ever hit her; I’ve always suspected he did, though it’s a thought I’ve routinely pushed away in the past. But then we’re on the subject of blood now, hers in addition to mine, and pretty much everyone else’s.

In each of her letters I found in that same attic box along with my old journal, Sarah again called me Frankie, in her broadly looping cursive, always Frankie. That is, up until that very last letter, when it was clear to her we had no way forward.

She disappeared from my life soon after. I never knew what became of her, whether still in America or back home to Belfast, whether free from that new abuse, or mired in some other even bigger form of it.

Google again: A couple of weeks ago, I impulsively searched under her old address, clearly expecting nothing after 35 years, and promptly encountering her same last name, and an actual phone number. I took a chance that next morning and made a blind call, and next thing I knew, I was talking to her brother, explaining that all those years ago …

I also mentioned how I was not trying to interrupt Sarah’s own life; I just wanted to know she was OK. And it sounds like she is, overall, having been back to Northern Ireland before again relocating to the States, this time to Cape Cod, and having endured several recent personal hardships, as we all eventually must.

Her brother was delightful, just charming and kind. A family trait, clearly.

“This has been a lovely call,” he said warmly, just before we hung up.

Way too late, I realized I truly had fallen in love with Sarah all those years ago; I feel that pang of real even right now, that peculiar afterburn of useless regret. She was everything good about Ireland to me, a simply beautiful human being from a stunningly beautiful place, a land of seemingly eternal green, of constant renewal, with all those many people who always stepped up to help me, their decency pressing itself forward, sometimes in the face of an awful reality it might never overcome.

Beyond that largely heartening news about Sarah, the cows are my favorite part of this story – the live ones, in that field, the ones that couldn’t have made me sick by just stopping by for a visit. And my weird pre-rain respite with them. And that lonely rural spot. And my on-and-off singing.

Ultimately, my unexpected brief connection with a bevy of gentle souls, all of whom hopefully lived to moo and mill about for many more days.

Since the whole 30-years-to-donate thing, I think of those cows, without fail, every time I think of giving blood. I couldn’t donate for all those years because of mad cow disease, yet during the peak of BSE in European cattle, there I was, singing to happy Irish cows.

It’s silly to think this, I suppose; I mean, there’s certainly no practical reason for me to. And maybe that’s why I do, the sheer silliness of it. Because life can be so goddamn hard, y’know? And with so many of us existing along borders and peripheries, atop fractures and other buried wounds, where so much less is certain, including life itself.

Silliness, I fervently believe, is simply essential.

I’m already signed up to donate platelets again, tomorrow morning, my birthday, in fact. This time, I plan to politely request a different Red Cross worker, and also, for my own warm blanket.

Some moments in life, I try my damndest to believe, don’t have to be so cold.

Comments

That right there was some reading time well spent. Having sung to my share of cows, I really related to that part. Cows just enjoy, and they don’t complain that you don’t sound like Willie Nelson or somesuch. They just moo gently. Then we …. we fuckin’ eat ’em… We deserve the BSE, no? Except, well … steak is so damn tasty …!!

Kudos on donating blood & platelets. They don’t let me do that anymore, ever since the seizures … something about the liability, the twitching, I dunno, maybe afraid I’m gonna break something. Probably smart. Dunno.

Sold more than my share during college, like, every effing day …. we had so many plasma & whole blood collecting companies around, and nobody checked with each other, you could quite literally donate every day if you wanted to … so I did. It gave me an hour or so to study … gave me a few bucks each day so I could afford to eat (tuition was expensive!) .. AND they gave you a piece of cake or banana bread and some OJ !! Kind of like winning the lottery! No mas. Now the only way anybody gets my blood is when the medico really wants to check something in it. Getting old sucks…

Ah … to be young again ….