Tributes have been piling up for Anthony Bourdain since news of his death last Friday morning in a luxury hotel in Strasbourg, France. As tributes will when death intersects celebrity, particularly when suicide is the culprit.

Tributes in this case are requisite, however. This was Anthony Bourdain, for chrissakes. Anthony Fucking Bordain!

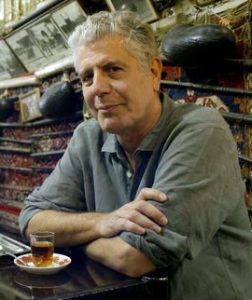

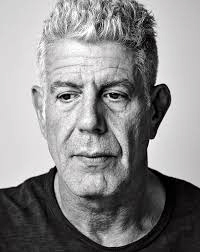

Former chef and restaurateur in cooking-cutthroat NYC. Ex-junkie success story. Best-selling author. Host of several enduringly popular food-centered TV shows, including the excellent No Reservations (the Travel Channel) and, most recently, the ever-exquisite Parts Unknown (CNN), both of which turned a love of drink and daring grub into an often ribald celebration of what’s best in humanity. A master interviewer and storyteller, Bourdain’s greatest gift may have been his boundless compassion for his subjects and, in what might seem at first a great irony in light of Friday’s worst-of news, for life itself.

I adored the man, at least what I could glean of him from his work, for his uncommon ability to make me feel as if I were savoring, right along with him, those remarkable physical, and emotional, places he routinely took his audiences. Bourdain was someone I could have been gay for, as the kids like to say. And all joking aside, I’m not joking. He was fantastic. Just fabulous. A real mensch. A gem.

In his later work, Bourdain came across to me as a one-man embodiment of the good available in us all. Gray-headed, tattooed, handsome and rode-hard weathered, he was the epitome of implacable cool. His abiding compassion was oven-baked with hot-buttered conviction, courage, and a boundless curiosity, yet he left unhidden enough ungarnished flaws to keep him authentic, and likeable as all hell.

At the very least, Bourdain made Americans seem as if they weren’t merely the global-sized pricks we so often can be when imposing ourselves across the globe. In this feat alone, his became a life I profoundly admired, and often envied: emissary for simple human decency. For me, this mission went far beyond inspired TV with revealing exchanges over local food and drink — from noodle bowls in Vietnam with a former U.S. president to street food just about anywhere often permeated with animal parts to cause mild horror in the uninitiated, and honest conversation with people you would never have cause to break bread with were you not as broadly inclusive as was Bourdain. He did human so very, very well.

We could all take a lesson from that, clearly.

By the time of his death, Bourdain’s life had long since become culturally significant, which is all any of us could ever hope for in our passing, if immortality was at all important to us when we were alive. His is a high-water mark that even tomorrow’s fickle tides will be hard-pressed to wash away.

But the egregious lack of brevity to follow isn’t really about him, except as reference. It’s really about the rest of us. At least a certain some of us. Certainly, one of us. Because, mostly, I suppose, it’s about me.

See, I recognized something uncomfortable about Bourdain almost from the start, even before I knew the whole addiction saga, or chanced to see him address what bedeviled him with blunt honesty, as he would on several occasions, both in print and in his shows. How terribly unquiet he was. That certain ineffable something around the eyes that belied the nearby laugh lines. That slight weary drop of the shoulders when cameras or crowd were perhaps forgotten for a second. The telltale way that praise rolled off him like it had never even registered.

For much of my life, I’ve been one of those no-club-that-would-have-me-as-a-member guys, often at the expense of potentially beneficial “opportunities” and “connections”; basically, if you’re fool enough to have me, then why in the hell would I possibly want to enlist in whatever it is you’re offering? Because your judgment is clearly suspect.

Unfortunately, there are those clubs, let’s call them, in which none of us gets to pick, or refuse, membership. Depression is one of them.

Bourdain’s passing has settled onto me like some leaden fog since my first reading the news Friday morning. Not just as a staunch fan of the man, but even more, perhaps, as a fellow card-carrying member of this loathsome association no member has ever willingly chosen.

Because Bourdain lived with depression, it’s now well known. He died from it as well, as is the same. I also live with depression. Though I am still here, clearly. But.

But for those of us who drew this particular short straw, there are those moments we can damn near convince ourselves we no longer have to pay our membership dues, that we can skip out on those lifeless meetings, to not be perpetually reminded of the rest of us so like, and unlike, ourselves. The fact is, however, that this soul-drowning dark never truly drains away. You may exist for years without the full knowledge it’s even rising there within you before its overtaken you in a slow inception, to begin reshaping you into some twisted golem, a kind of animate ghost, whisping in and out of your own view, and all the while unable to comprehend what’s haunting you as the rest of the world smiles and goes on about its usual business.

Some people never figure out any of this before they succumb to the disease regardless. The rest of us may discover the name for our symptoms with the help of a doctor, a therapist, a family member (in my own case), a friend. We may then even begin to imagine that some combination of drugs and therapy, of immersion in exercise, art, self-medication, sex, music, whatever, will transport us back finally to the other side of the street, to where denial may blessedly win again, and we need no longer pass by that nightmare clubhouse, to inevitably catch sight of ourselves in the window, mere afterburns of what we have increasingly less faith we used to be.

I never wanted the name “depression.” It explained at once so much about me that I am still hard-pressed to admit to. Because once I did finally concede to accept that this was me, which I did not do for many years, at the expense of so many things important to me, it was also admitting that my mind was inescapably broken, the chemicals in me all catawampus, and that I would always, to some extent, be recognizing myself in that wretched goddamn window, no matter how wide the street between us might become.

When handbag-designer Kate Spade took her own life just days before Bourdain, it registered with me in the way celebrity suicides generally do if I have no overt connection with the person. A feeling of abrupt unsettlement, which dwindles as a distinct incident once the typical hand-wringing and questioning has subsided: She had so much going for her. How could she not have been happy? Etc.

You encounter a lot of chatter on talk shows and in self-help books about “choosing happiness.” Nice work if you can get it, I suppose, but not all of us are given that choice. For most of us in this lousy-ass club, joy itself is an uphill fight, that whole exhausting Sisyphus thing. (That said, fuck you, Tom Cruise, and the sanctimonious Scientology horseshit you rode in on.)

Growing up, I watched my angel of a mother endlessly battling to rise above the deep dark well of pain and sadness at her core, through daily acts of personal affirmation and religious assertion, books on positivity and seeing the world for the sunshine and not the shadow. Always trying to look through light, to yes, turn that frown upside down. She failed, repeatedly, but oh, how she tried, beautiful creature that she is. Then a few years ago, dementia blindsided her in a crippling onslaught of forgetting, and then my dogged old man, 60 years her partner, died late last September following a lengthy battle with a faulty heart. My mother has nothing now left to fight with, when the tide turns, and the dark water again rises. As it will. As it does. As I guess it must.

Thankfully, there have been only a few times in my own life when the darkness has become so overwhelming that even the indomitable Rabey force of will — that part of my fight-against-the-dying-of-the-light father in me, his career-Army immigrant-son drive to just get up and keep going in spite of every insult and hardship, no excuses, just get on with it — even that was barely enough to force me to jut my chin back up from where I huddled useless on the floor, to beg life’s next punch. I was down pretty close to the count, contemplating how best to get the countdown to actually stop. To. Just. Please. Stop.

Don’t mistake my use of metaphor here for attempting to add any drama to this; nothing I can say, in any way, will capture the living tailspin of this disease. There is not a goddamn thing romantic or poetic in this “darkness.” This isn’t some rom-com upswell of bittersweet music and fleeting lesson-learned sadness, no Goth-kid dalliance in Kat Von D Studded Kiss Kreme lipstick.

Depression is a thing that rides you. It sinks its poisoned teeth into you, and may ultimately swallow you whole if you cannot outmaneuver the life-sapping bleakness. It can feel at times like it’s stealing even your own shallow breaths from you as it sucks the happy out of everything, replacing it with an almost palpable emptiness, a vast blank vacuum of the self.

While in the deepest throes of it, depression becomes everything, all that is you, framing every action and reaction; there is nothing else. And yet this isn’t you, right? And yet you continue to exist, lost inside yourself, bound inward by a dense miasma of nothingness you cannot fathom your broken way beyond. Even sitting upright becomes an effort of maximum will.

It’s as if some of your own death has somehow seeped into you, too early, and you cannot get it back out.

Or so I’ve heard. Ha, ha.

I can’t speak for anybody else, and certainly not for Spade or Bourdain, nor for the Sylvia Plaths, Kurt Cobains, Spalding Grays, the magical Robin Williams, et al., and I wouldn’t presume to try. This chemical affliction is as universal, and unique, as each person. Yet it has been my experienced observation that those of us molded out of darker stuff try that much harder, in our better moments, to seem as though we’re traveling instead in light, because if others don’t see our perpetual falling, falling, falling, then maybe, just maybe, we aren’t doing that badly after all.

There is a mindset that sets in, of not wanting to bring those people we care about down to our own dolorous level. Of trying to keep what’s purest to us free of our fundamental grief, which I myself can never do, and which only makes things that much worse for everyone involved, a hideous cycle that certainly did wonders, for instance, for my own first marriage (and Tracey, I am truly sorry).

It’s not a lack of sincerity in our dispositions, but an abiding desire to rise into the moment, to bask in whatever light we find, wherever and whenever we chance to find it. This effort alone often appears to others as an abundance of personal warmth, of a vivacity of presence. Because it can also, I think, foster in us a heightened appreciation of those things that are good. Because too often, most other things are terribly otherwise.

When I was young, before this thing came to live so vividly inside me, as heredity always hinted that it might, I was often chided good-naturedly by friends for my wild exuberance. I get it now. What it likely meant, I mean. Because even then, life was peppered with prolonged bouts of consuming sadness, which I honestly wrote off to typical teenage/hormonal angst. And then adulthood showed up, and the dark hours grew longer. And then, longer still.

Bourdain was frequently described as the warmest person in any room. He’s just the opposite now. And yes, that is horribly crass. But.

But the whispery presence of death, for many of us, is just part of it. And the force of keeping up the will to fight always fails at some point, some harrowing flashpoint, and how we navigate those hellish dips into the darkest nights of the soul defines if there will be even a hint of light tomorrow.

I’ve lived through a dear friend’s suicide; brilliant and funny, he was gone by his own hand at 21. I think of him still, almost daily. The true brutality of suicide is in what’s left behind, the lives that persist trying to find sense in a bright world for an act that arose out of a place of unrelenting darkness. And if that doesn’t speak to the desperation of the act of suicide itself — the knowledge you will devastate, and yet you are still convinced your absence is the best thing for everyone — then I cannot imagine what does.

For years that has been my own mantra, when things have gone so far south: There are people who will have to go on without you, and it will hurt these loving and devoted souls, less through time, but always. Even as the shitheel you can so often be, bub, there are people who genuinely love you. They will inevitably question why their love and care for you were not enough, which no one should ever have to do. And they will never fully understand, if they are not also members of this rotten club, that there are times when nothing is ever enough, and at that point, nothing itself becomes seductively attractive.

On his best days, Bourdain probably was convinced this outcome could never be his. He had a kid, for fuck’s sake. A loving girlfriend. Many people depended on him. His was a life so many of us envied. But.

But this one time, my worst time, not too long after the implosion of my first marriage and the realization that I had no fucking idea what constituted myself, and why I should continue for another moment to exist, it was only the fact I had two cats to feed that kept me here; I trusted no one else to love my irreplaceable furry companions enough, and to care for them as I did.

these dog days

i don’t know

anymore but the cracks

the cracks, and these two cats

have to be fed

some days, other

days i cut myself, careless, see red

rings, circles, years, and the frightened

black one mews i need, i need

nights, there are things eating

in me, of, through me

i don’t know where

and the white-and-black one, the boy

circles my face with his tail

stretches, fur belly up, a something

smile i can sense, in stray window light, can see

his paws touch the air

— fwr, 2004

Really, that was it, just that. And when I slowly surfaced out of this blackest pool, with much pharmaceutical assistance, those adored and wildly individual animals became, in the aftermath of my very near absence, like two parts of my own familiar, living talismans of life itself. So much so that when they both died two years ago, their deaths, within a month of each other, upended me to my very essence, far beyond even the tangible absence of their singular friendships and unwavering affections.

That combined loss was like having whole chunks of that part of me that adhered to being alive violently ripped away, my soul made manifest and then twice gutted. I floundered dangerously in the loss, as profound as any in my life.

Consequently I went back again on antidepressants, for who knows what number of times. It was long overdue at that point, but my caring wife Lisa recognized how far and how fast I was plummeting, after several years of enduring me having already fallen so far below my already low baseline. I doubt now I will ever be off the meds again, and OK. Too much intolerable sadness under the bridge. So yeah, OK.

I am, as Matt Berninger with The National once put it, “on a pretty good mixture.” And I do love that phrase. It sounds so goddamn happy.

But let me be clear on one key point for those of you out in the studio audience: Nothing exorcises this demon. Depression is not the common cold; it’s more like some bastard of a virus that never goes fully dormant, ever waiting for the right wrong trigger to flip it back on, to sink its black fangs back into you again. It’s just that now the cracks in me don’t feel quite so wide, or as unfathomably deep, such that mostly I can navigate over and around them.

For even this slight respite, I am grateful. So very grateful.

I am an atheist. I see no heavenly reward in death, any death. I see only quiet, and I am good with that. And I understand too well how sometimes the idea of no longer being caught in the maelstrom, of flailing forever against the insistent dark, the incessant clamor of doubt and uncertainty, loss, anxiety, physical pain, the sense of fraudulence, the whole entropic chaos of simply being aware, whatever, can cascade into a moment, that please-never flashpoint moment, so resolutely to be wished against.

Pure existential exhaustion, when the idea of no more becomes The Only Idea Left. That, goddammit already, just let it stop. Let it be quiet now. Let me be quiet now. Let it all just stay quiet.

Bourdain is a too-real reminder for those of us who live our lives in the constant shadow of an insatiable dark, that there can be a time when nothing anymore can ever be enough. That the hole can quickly become the whole, to where nothingness itself becomes everything. And it only takes one wrong moment to get death right.

I have never been sure what peace might feel like. So I wish for you, Tony, my never-met fond amigo, great guide in this life to the immense and fleeting grandeur of life itself, that when your own quiet came, that you heard what you needed it to be.

<87 post likes from original blogsite>

Comments

Beautiful, thank you so much for writing this.

Author

I am grateful you found it worth your time, and for your then taking the time to say so.

OMG!!!! Frank. Thank you so much for this article. Going through a dark time myself right now and I’m hating the constant tears, but at least I CAN cry. The depth and feeling and truth in this article .. I’m shaking my head in amazement that one human being can articulate this so well and so easily understandable. I love you my friend. Keep hanging in there. We all need you!

Gut wrenching amazing split your heart wide open beautiful!

Thank you!

Author

Thanks, Greg. Had not actually even intended to write this, but some things just kinda demand to come out.

You’ve hit the nail here and the resulting cracks in the foundation may be enough to let the light creep in, Frank. Will seek answers from his death as long as I draw breath. None makes sense until I read this article…. then the light dawns slowly. All I can contribute here is admiration for as succinct a word smithing as ever I have encountered, on a subject I’m still learning to comprehend. Big love for you, my good friend.

You said it all with this one, my friend. I’m prettty done with the ‘choose happiness’ thing myself. The struggle against the darkness is real, and the fight is the whole goddamned point. I reckon that creating things is something that takes the edge off, makes us real, and, somehow, proves we are/were here. This piece does just that.

Peace.

JMR

Frank, thank you for this beautifully written piece. You put into words what many of us cannot.

To remind you, there is a great, big club of your family and friends (many of whom suffer from the darkness). You belong to that club of people that love you, get you, and want the best for you, You’ll never escape that club, whether you want to belong to a club that wants you or not. And just for your information, we’re damn good people.

Well written! Thanks for sharing your thoughts about that side of life many of us experience but most often do not share. It is not a small club by the way. With age and time I have become increasingly aware of how the openness of others have helped me acknowledge and cope with this virus of a dark side that pharmacuticals only chip at providing control.

Two of your descriptions capture the frank (no pun intended) reality of the battle all of us “club members” face.

“Nothing exorcises this demon. Depression is not the common cold; it’s more like some bastard of a virus that never goes fully dormant, ever waiting for the right wrong trigger to flip it back on, to sink its black fangs back into you again.” and

“Bourdain is a too-real reminder for those of us who live our lives in the constant shadow of an insatiable dark, that there can be a time when nothing anymore can ever be enough.”

Dear Frank,

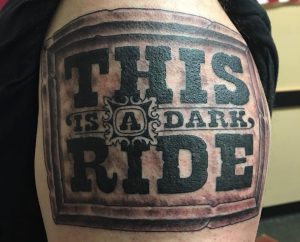

You are so soulful and brave to talk about the wounds those cracks have caused. Beautiful!! I am going to look at depression differently and you have touched on this “dark ride” is such a different way. I adore you for sharing this with me. You are tall in my book.